14 Sep Could 3-D Printers Help Parents Better Understand Children’s Heart Conditions?

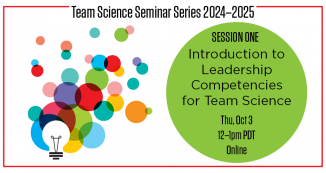

When Dr. Sujatha Buddhe, a pediatric cardiologist at Seattle Children’s Hospital, communicates with parents about their child’s congenital heart disease, she draws pictures. “We try to show them, ‘These are the four chambers, and this is where it’s defective.’”

But anyone who has flipped through an Anatomy 101 textbook knows that it’s difficult to understand the heart with a two-dimensional drawing. For parents of children with congenital heart diseases, those drawings can seem even more complex.

“A lot of studies show that parental understanding of congenital heart disease is limited,” Buddhe said. “It’s hard enough for medical students and fellows to understand what we are drawing on the pictures. It’s even tougher for parents who have no idea what a normal heart looks like.”

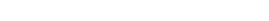

But what if parents could actually hold their child’s heart–a 3D-printed model of it, that is–in their hands?

It’s hard enough for medical students and fellows to understand what we are drawing on the pictures. It’s even tougher for parents who have no idea what a normal heart looks like.

Advances in 3D printing technology have made it possible to print life-size and life-like models of the human anatomy, including congenital defects of the heart. A couple studies have found that using these models during consultations between parents and cardiologists enhanced communication, improved parents’ understanding, and helped reduce the stress of the consultation.

But creating the models is expensive and not covered by insurance, Buddhe says. A more cost-effective, but still visual and three-dimensional, alternative is using a virtual model on a laptop or iPad during consultations. Unlike the 3D models, parents could also keep the virtual model file and view it on their personal computers or tablets.

Buddhe’s study aims to find out if 3D and virtual models improve communication around congenital heart defects and if there is a difference between the two techniques.

Parents in the study will first receive a consultation with the traditional 2D drawing followed by a a later consultation, when physicians explain the heart condition using either the 3D or virtual model.

When we started the study, we were still trying to figure out the primary endpoints and how to make it happen in one year. And ITHS definitely helped with the power analysis.

A short survey will be given to parents after the consultation to gauge how effective the model was and if it enhanced communication and understanding. Physicians will also complete a questionnaire. Buddhe also wants to know how the new technique affected physicians’ workflow.

The study’s primary endpoint is testing feasibility and acceptability, Buddhe said. The secondary endpoint is trying to see if the new techniques improve parental understanding and if there is a difference between the two.

To define these endpoints, Buddhe worked with Dr. Michele Shaffer, Co-Director of the Institute of Translational Health Sciences’ Children’s Core for Biomedical Statistics.

“When we started the study, we were still trying to figure out the primary endpoints and how to make it happen in one year,” Buddhe said. “And Michele definitely helped with the power analysis. With very limited data out there, it was hard to do this analysis.”

Ultimately, Buddhe hopes these 3D and virtual models can extend beyond patient communication and improve teaching for fellows, and medical students and management of patients in post-op.

“When patients come back to the ICU, the surgeon who did the surgery knows exactly what he did. The cardiologist understands. But the nurses, they are the ones taking care of these kids,” Buddhe said. “Their understanding, as well as the medical students and fellows there, of congenital heart disease is limited in terms of what happened pre-op and post-op. We are hoping to extend this into the ICU level and improve education about congenital heart disease.”